The World Health Organization has referred to obesity as “one of today’s most blatantly visible – yet most neglected – public health problems”. But excitement is now rising around new appetite-suppressing medications with public health organizations hopeful that these treatments may help tackle this growing epidemic.

The new treatments, known as Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (common brands being Wegovy and Ozempic), shot to fame with rumored off-label use by an array of celebrities with some striking weight loss results. The medications have now been approved for prescription for weight loss in the UK, the US and Canada, with the Danish manufacturer of the leading brand struggling to keep up with demand and with its stock value now exceeding the GDP of its home nation, famed for its butter and bacon.

What are GLP-1 receptor agonists?

GLP-1 receptor agonists were originally developed to treat type II diabetes. They act by mimicking a hormone that stimulates the body to produce insulin, which reduces blood sugar levels after eating. These drugs also reduce appetite, possibly as a result of slowing the movement of food into the small intestine. Studies have shown these drugs can lead to significant weight loss.

There are a variety of GLP-1 receptor agonists available1, the most common being semaglutide (brands of which include Wegovy and Ozempic). The majority of these drugs are currently administered by regular injections and are commonly accompanied by various gastrointestinal complaints. They are seen as long-term treatments rather than short-term fixes, but given their high price and unpleasant side effects, many find them challenging to maintain for long periods.

The growing obesity epidemic

Obesity (defined as a body-mass index over 30) has doubled over the past 25 years. It now affects large swathes of the populations of the US, Canada and the UK. By 2016, the proportion of the adult population estimated to be obese had reached 37%, 31% and 30% in the US, Canada and the UK respectively, with the highest concentrations in 45-75 year-olds. The likelihood of being obese does not seem related to socio-economic status.

Source: WHO data, downloaded from Our World in Data, Nov 2023

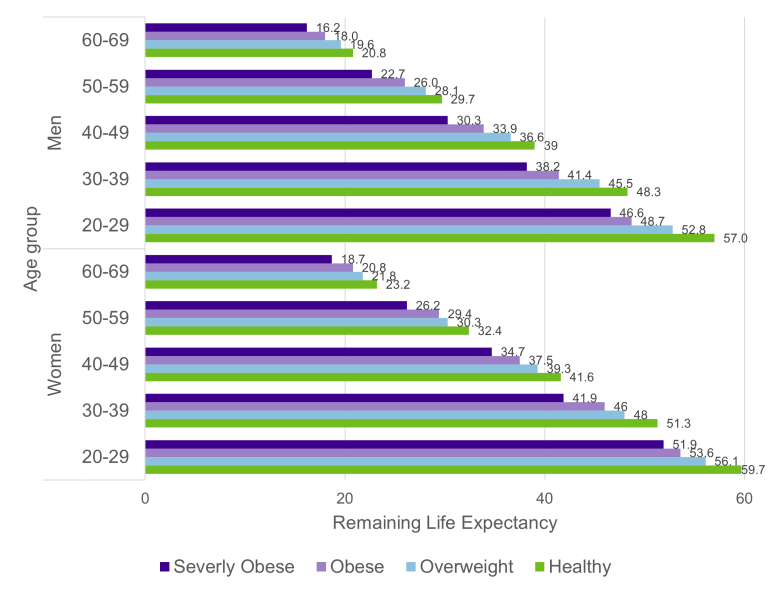

Overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk of a wide range health conditions including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, osteoarthritis, high blood pressure and high cholesterol. With these effects, it is not surprising that overweight and obesity result significant reductions in individual life expectancy, particularly for younger people. The chart below shows the results of a 2019 study of Australian adults that estimated differences in life expectancy by weight classifications; focusing on the age groups with the highest propensity, obesity reduces period life expectancy in 60–69 year-olds by 2-4 years and in 50-59 year-olds by 3-6 years.

Source: Lung, T., Jan, S., Tan, E.J. et al. Impact of overweight, obesity and severe obesity on life expectancy of Australian adults. Int J Obes 43, 782–789 (2019).

What could this mean for pension plans and insurers?

If we assume that these treatments could help around a third of the population manage their weight from obesity into the healthy range, life expectancy could increase by around 1-2 years for 50-59 year-olds and 0.33-1.33 years for 60-69 year-olds. This could equate to an increase in liabilities for a pension plan or pension risk transfer portfolio of around 4%. To put this into perspective, in the UK, statins (one of the major success stories in public health over the last 30 years) have been estimated to have increased national life expectancy at age 70 by 2-3 years between 1987 and 2010.

Pension plans and insurers trying to assess this potential impact will need to consider whether individuals they are valuing have a higher or lower propensity to obesity than the general population, and how accessible and appealing these types of medication will be to them over the long term.

If GLP-1 receptor agonists were appropriate for most people and became widely available and adopted, it is possible that significant advances in public health could be achieved. But this is a big ‘if’, and, in their current form, it seems unlikely that these treatments will become widely adopted over long periods. We will be monitoring the developments of these treatments closely in the coming years.

What do you think?

Are GLP-1 receptor agonists a silver bullet for obesity or a small step in the long road to helping people manage their weight? Do you know anyone with experience of these drugs? What is their verdict?

For more discussion, please follow us on LinkedIn and join our Friends of Club Vita discussion group.

1 For a list of such drugs currently available in the US, see this summary from RGA.