Read our first mega trend blog where Douglas Anderson discusses UK longevity inequality.

My annual health check

One day last week, I spent three hours reflecting on the healthiness of my lifestyle, prompted by a string of health indicators. It’s become an annual ritual, which started when I was in my late 40s, when I was shocked to learn that my sprightly father-in-law had been diagnosed with stage 4 prostate cancer. Trevor was a stoic Brit who did not want to trouble the busy doctors and nurses of the NHS.

My health check is a privilege that is not available to all. I have the knowledge to know it’s a wise thing to do, the motivation to want to improve, and the money to pay the bill. Although health tests are available for free on the NHS, their frequency and coverage is lower and, perhaps most importantly, the amount of discussion time to explore how to change stubborn habits, is much reduced.

What I’m describing here is an example of how health inequalities play out in practice, even in a society that is proud of its free health care at “point of need”.

Past performance

In the recent past, the gap in life expectancy between the rich and the poor, underpinned by such health inequalities, has increased in the US and Canada, as well as my homeland of the UK. Indeed, this Lancet article sets out the scale of the UK’s challenge as the sick man of Europe.

The question on many people’s lips is, will this gap shrink or grow in the coming years? To help us think about the future trend, let’s focus on the extremes ends of the income distribution.

Have the highest socio-economic groups reached their limit?

I think not. They don’t appear close to any biological limit on life. Future longevity megatrend blogs will discuss the strong pipeline of amazing new health technology that will start to be deployed in the next decade (such as more personalised therapies enabled by the genetic revolution). Initially, these longevity innovations are likely to be expensive, and only accessible to those with more disposable income or savings. When new thinking has emerged in the past, the wealthiest have shown themselves to be more likely to be early adopters, only later creating a social cascade effect down towards the poor.

Given this, to close the longevity gap, our leaders (both politicians and employers) have to be bold in their ambitions to “level up” the poor.

Are there bigger gains in lifespan to be found in prevention, not cure?

Scientists now regard lifespan as the outcome of the lifelong process of ageing. Ever more persuasive research shows that the healthiness of your lifestyle (exercise, diet, alcohol, smoking, sleep) affect the pace of your ageing. So, if we really want a guide to lifespan in a decade or more – and, in particular, the gap between rich and poor – we should search for evidence of improving health. In other words, is the message that prevention is better than cure really getting through, particularly in harder to reach groups?

For the rest of this blog, let’s take a deeper dive in to UK developments.

The UK government latched onto the problem in 2018, forced by the upcoming economic challenges of ageing baby boomers: a problem that has been evident since the 1970s. In "Prevention is better than cure", it set out a target of five more years of “healthspan” (that is, disability-free life) by 2035, along with a reduction in inequality. The vision is bold and the target (unusually long-term for politicians), is stretching given the incremental nature of health gains.

How do different people embrace prevention?

To see how different socio-economic groups embrace preventative health measures, we can look at healthiness of residents of small areas, based on postcodes grouped together according to their level of social deprivation.

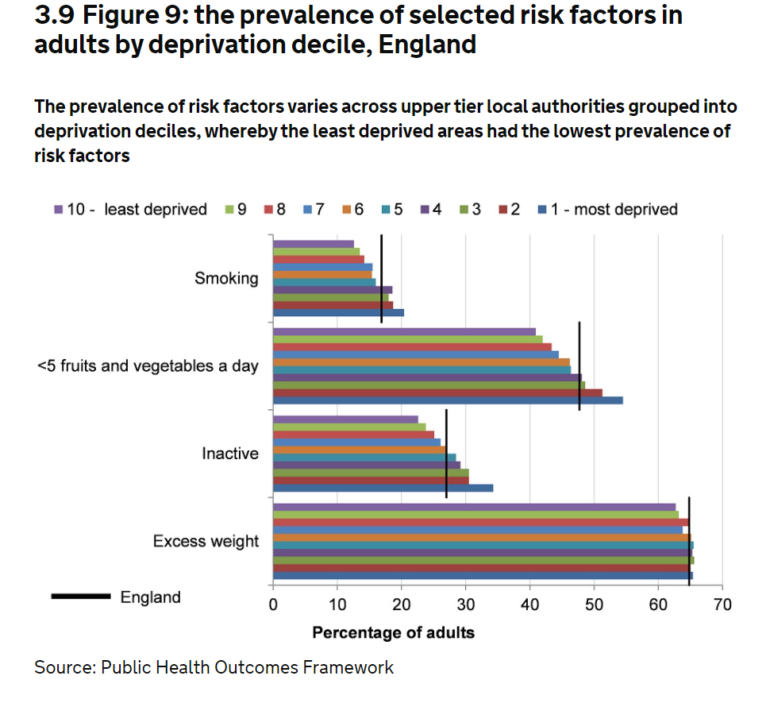

The infographic below shows the position in England, drawn from a series of different sources around 2013-2015. You can see the stubbornly steep social gradients in propensity to smoke, eat healthily and take exercise. The only thing that looks like a level playing field is the likelihood of being overweight: with a staggering two in three residents of all areas, irrespective of level of deprivation, being overweight.

Chart source: UK government, Chapter 5 "Inequality in health"

My search for more recent data took me to Public Health England, who, to its credit, has developed a great interactive website covering a range of different indicators of health. Sadly, many out the data sources remain old and none revealed any great grounds for optimism. In the three years since the UK government created its goal, the UK seems to have gone backwards (even before taking COVID into account).

There are bigger gains to be had for the poorer people in society, but what will encourage the changes that are needed?

Show us your money

The policymaking is rich in ideas, with the emphasis squarely put on prevention, rather than cure.

The 2018 conservative-led initiative has morphed into a bipartisan group, the All Party Parliamentary Group. This collective action is to be applauded, but where is the funding?

Employers can – and should – be more proactive in tackling the problem at early ages. I like the sound of Business for Health’s campaign to get ‘Health’ into Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) frameworks - that is, ESHG. This would create a four-pronged social change programme for a more sustainable society.

To make such a huge difference in a short period, there would have to be major investment in public services, requiring an appetite for bold, redistributive tax policies, and a willingness to discourage unhealthy habits through targeted taxes.

The NHS should be the perfect delivery mechanism to improve the nation’s habits. But, sadly COVID has highlighted just how little spare capacity exists. It is too busy trying “to cure” to spend enough resources on prevention.

To turn the UK around, I reckon you need significantly more investment in reducing health inequalities, persistent effort and more patience.

The bottom line: UK longevity inequality looks set to continue rising over the next decade

I wish I could be more optimistic, but I struggle to see how the UK government will be able to narrow the healthspan gap sufficiently fast to have any material effect on narrowing the lifespan gap in the next decade. Remember that the pattern of future lifespan reflects the delayed outcomes of the healthiness of past lifestyles (so the historic health gradient data is actually more relevant despite its age). Even if the collective action can nudge more of the poor into materially healthier lives by 2035, those gains would only slowly filter through into a future narrowing of the lifespan gap.

To all the Brits, I hope I am wrong and will be glad if anyone wants to hold me to account in 2031 (when I very much hope to still to be working!).

Wherever you live, what is the outlook in your country?